Download the handbook

Download the handbook

Download the handbook

Download the handbook

In this blog series, Public Health Wales’ Violence Prevention Programme Lead, Lara Snowdon explores some key challenges that the UK and Welsh Governments face in their ambitious commitments to prevent violence. This third post focuses on four complex challenges involved with driving population-level violence prevention, through a public health approach.

Earlier posts highlighted the importance of focusing on primary prevention – tackling the root causes of violence before it happens – and the evidence-based strategies that show promise for primary prevention interventions. However, even with clear direction and proven methods, there are significant barriers to overcome if we are serious about reducing violence at scale and at pace.

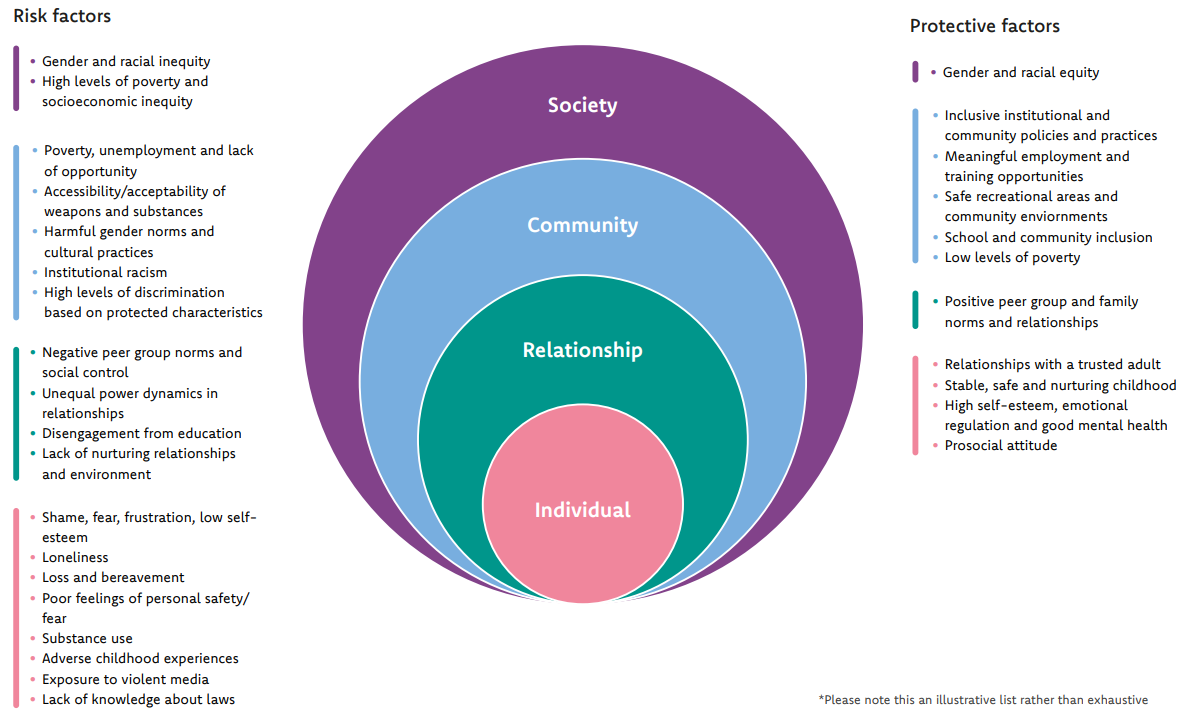

Violence is not a single issue with a single cause. It is shaped by a web of social, economic, and cultural factors – including poverty, inequality, harmful gender norms, childhood adversity, and structural discrimination. Effective prevention must navigate and address these intersecting challenges, often requiring long-term, cross-sector collaboration that goes beyond short funding cycles or political terms. However, recognition of this complex inter-relation of risk and protective factors (through a socio-ecological lens) is an important step in developing and designing effective approaches to prevention.

Violence prevention cannot be achieved by one agency, sector or intervention alone. It requires a whole system approach to address the structural drivers of violence as well as individual risk factors. In Wales, the Wales Without Violence Framework (read here) offers a clear, public health-informed structure for this kind of collaboration. Developed through co-production, the Framework helps align work across local and national levels, and advocates for trauma-informed, evidence-based practice through the nine strategies for violence prevention. Whole system approaches like this make prevention everyone’s business – and are essential if we are to deliver change at the scale and speed needed.

Consistent and robust data that provides insight into the prevalence of different forms of violence is essential. Without robust, nuanced data, it is not possible to prevent violence in any meaningful way, as we don’t know what we are measuring or benchmarking against. In Wales, significant progress has been made to improve the quality of data used to understand violence. However, there are still gaps in our understanding of prevalence and intersectionality. The Violence Prevention Team in Public Health Wales now have data sharing agreements in place with all Welsh Health Boards to receive anonymous information on emergency department (ED) attendances where violence with injury has been identified. This is a breakthrough for violence prevention in Wales, with data being made available to partners through bi-annual Violence Monitoring Reports and through our Violence Prevention Portal (alongside a range of additional administrative datasets).

However, administrative data – which tells us about those who seek access to services – can only tell us about the ‘tip of the iceberg’ in terms of prevalence. At present, survey data on violence (through the Crime Survey for England and Wales) is not routinely disaggregated, which obscures the specific demographic, social, and policy conditions in the Welsh context. As highlighted in our recent publication led by Dr Polina Obolenskaya from the VISION Consortium (read here), this limits the ability to target interventions and measure progress effectively.

Additionally, across datasets there are significant gaps in reporting protected characteristics, such as disability, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Without this data, programmes risk being designed without an adequate understanding of the intersectional nature of violence and thus, without the insight needed to support those at highest risk. Robust, representative survey data which presents an accurate picture of levels of violence would be a significant next step for both Welsh and UK Governments to measure ambitious objectives for violence prevention.

Wales is a nation with its own parliament, the Senedd, and government, with powers that have been devolved from UK government in Westminster under a series of legislative Acts. Key policy areas relevant to violence prevention that are devolved to the Welsh Government include health, education, housing, and social care while England and Wales policy and legislation for crime and justice matters remain primarily under the UK Government’s Departments of the Home Office and Ministry of Justice. This leads to complexity for services operating in Wales, which often sit between overlapping systems, funding streams, and priorities. One example is the Serious Violence Duty, which applies in Wales but must be implemented alongside existing Welsh legislation such as the VAWDASV (Wales) Act 2015. Wales would benefit from better coherence across devolved and non-devolved responsibilities, with policy and funding that respects the specific needs and structures of Wales. The Justice and VAWDASV Blueprint approach in Wales attempts to do this, bringing ministers and departments from both governments together, with leadership from Welsh Ministers and Policing in Wales; but still the prevailing issues of the jagged edge of devolution in Wales remain.

Similarly, VAWG strategy and policy in the UK (violence against women and girls) is largely delivered in isolation to policy on other forms of interpersonal violence despite shared drivers and prevention opportunities. In our research with children and young people (read here), we found that violence is not experienced in the way that these policy silos suggest. Instead, experiencing childhood adversity, including domestic abuse in the home may increase the risk of involvement with gang violence, for example. Likewise, for a gender diverse young person, sexual harassment and bullying might represent concurrent forms of discrimination. Whilst there are important nuances and specialties within these policy areas, we can’t risk losing sight of children and young people’s lived experience and these policy areas must be more joined up if we are to effectively prevent violence.

The Domestic Abuse Commissioner has highlighted this critical need for joined-up approaches (read here), noting that there is a growing body of evidence showing co-occurrence between youth violence and experiences of domestic abuse (see Jade Levell’s research – read here). Given these connections, there are clear opportunities to develop responses that address different types of harm holistically, including understanding shared underlying structural factors and adverse childhood experiences. The Commissioner’s research found that the Serious Violence Duty and the discretionary nature of local definitions of ‘serious violence’ has reinforced siloed thinking. Despite the inclusion of domestic abuse in the legal definition of ‘Serious Violence’, in practice, this has not translated into a joined-up strategic response, with a lack of collaboration between serious violence and domestic abuse professionals limiting coordination and common understanding as to best practice.

The evidence is stark: violence is experienced disproportionately. Understanding these inequalities is crucial for effective prevention, but it also presents one of our most complex challenges. As we’ve seen in the previous sections, violence is deeply embedded in social structures, our data systems often fail to capture the full picture, and policy doesn’t always recognize or seek to redress these inequalities. Using an intersectional lens is crucial to tackle inequality. Without this, equity cannot be achieved for all people in Wales.

Violence follows patterns of inequality that mirror broader social injustices. Children and young people face significantly higher risks than adults, with those in the poorest areas of the UK seven times more likely to be involved in violent crimes as a young adult. Gender remains one of the strongest predictors of both perpetration and victimisation, with men significantly more likely to be perpetrators across all forms of interpersonal violence. Globally, one in three women have been subjected to intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime, while 97% of women aged 18-24 across the UK report having experienced sexual harassment in public spaces.

The picture becomes even more complex when we consider intersecting identities: gender diverse individuals, disabled people, and those from Black and minoritised ethnic groups all face disproportionate risks. Perhaps most concerning is the cyclical nature of violence which reproduces these inequalities – in Wales, people who have experienced significant adversity in childhood are 15 times more likely to experience violence as an adult.

This intersectional understanding is not just about documenting inequalities – it’s fundamental to effective prevention. The data gaps we discussed earlier often miss these nuanced experiences, while the policy fragmentation outlined in section 3 can leave those most affected by social inequalities falling through the cracks. Violence prevention that fails to consider intersectionality is not prevention for all. We need services and strategies that are inclusive across the life course, designed with an understanding of marginalisation, identity, and inequality. Only by acknowledging and addressing how social structures create the conditions for violence can we hope to create truly effective, equitable violence prevention. The ambition to halve violence in a decade can only be achieved if we ensure that reduction benefits all communities.

There are many challenges involved with preventing violence including funding, political will, and the policy-implementation gap, for example. This blog has focused on four key challenges for preventing violence through a public health approach. Halving violence in a decade is not a simple task – but the ambition matters. By naming the challenges as well as the solutions, we can build a more honest, grounded, and collaborative approach to violence prevention. What do you think are the main challenges for violence prevention?

In our next blog, we’ll look at global examples of violence prevention strategy in action and consider what can be learned from effective approaches.

Reference List

1. Levell, J. (2022). Boys, childhood domestic abuse and gang involvement: Violence at home, violence on-road. Bristol: Policy Press Scholarship Online.

2. Mok et al., (2018). Family income inequalities and trajectories through childhood and self-harm and violence in young adults: a population-based, nested case-control study, Lancet Public Health, 3(10).

3. UN Women UK. (2021). Prevalence and reporting of sexual harassment in public spaces. Survey conducted in partnership with the All-Party Parliamentary Group on UN Women. Released March 2021.

4. Bellis, M.A., Hughes, K., Ashton, K., Ford, K., Bishop, J., & Paranjothy, S. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences and their impact on health-harming behaviours in the Welsh adult population. Public Health Wales.